You’ve Got Options: Revisit Your Retirement Savings Before It’s Too Late

With so many corporate executives accumulating millions of dollars in nonqualified deferred compensation (NQDC) plans, it’s time to revisit the importance of these plans to provide needed retirement savings.

However, when NQDC plans become the topic of top-level executive meetings, company leaders often long to understand plan fundamentals far better than they do.

In truth, these plans are not as complex as they seem. Yes, they do come with a language all their own that can initially confuse even sophisticated human resource executives. But at their core, NQDC plans are simply a way for the highly compensated executive to save money on a tax-deferred basis.

This post stretches beyond a basic understanding of NQDC plans and focuses more on today’s needs for retirement planning compared to earlier generations. For a comprehensive understanding, please download our master paper on “Designing Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Plans to Competitive Advantage.”

The Why Behind NQDC Plans

Executives carry a disadvantage when saving for retirement. The rules imposed by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) limit the amounts that highly compensated executives can contribute annually to qualified plans such as the 401(k).

For example, the “highly compensated” are restricted to a contribution into the company’s 401(k) of not more than $18,500 ($24,500 if you are over 50) in 2018.

ERISA was enacted to protect the rank and file from potential abuses by senior management, and in that regard, it has been a success. But ERISA also placed restrictions on the senior management group, even though these highly compensated individuals produce relative value to the business enterprise.

Companies must find ways to attract and retain these highly valued employees if they are to succeed in their growth objectives and create positive returns for their shareholders. To address the inequity created by ERISA, and to provide a valuable executive benefit, companies began to offer savings plans considered “nonqualified,” meaning they are exempt from the “qualified plan” limits imposed by ERISA (e.g., $18,500 limit in 401 (k) plans).

NQDC plans help to level the playing field when companies work to attract, retain and reward top talent in the company. Eighty-five percent of the Fortune 1000 offer NQDC plans because no other executive benefit costs so little and provides plan participants so much.

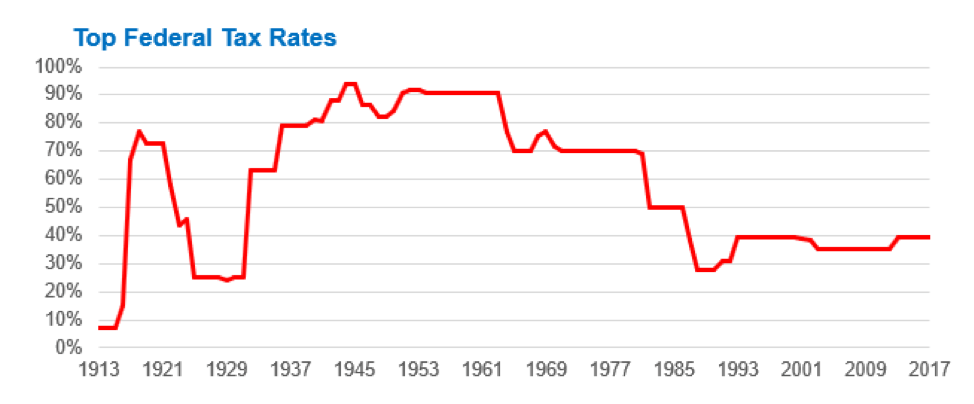

However, most of these plans were adopted before the enactment of 409A, a piece of legislation that dramatically changed NQDC plans, especially regarding benefit security. What’s more, income tax rates were much higher in years’ past as noted in the chart below:

In a recent blogpost, What We Learned from Enron and Chrysler, you see the striking change: The 409A legislation. Now, factor this into the mix— as Generation X and Y began climbing the corporate latter, their needs took on a different complexion than their parents’ plans. For instance, the tendency to remain with one employer over an entire career has, for the most part, disappeared.

Two Generations Deferring Comp

At this juncture, we need to share the experiences of a father and his two sons, all three of whom are participating in NQDC plans.

The father, we’ll call Joe, like many people in his Baby Boom generation, worked at the same company for 30 years. In 1988, when he was only 45-years old, he began to participate in the company’s NQDC plan. Even though his deferrals fluctuated year-to-year, based on his bonus, we’ll use the illustration of a flat $50,000 per year so we can make a fair comparison with his sons.

As discussed in the Enron and Chrysler post above, Joe faced very little creditor risk because his plan carried a “haircut provision,” which allowed him to access his money at any time, regardless of his elections. Another important assumption to make a fair comparison, Joe selected the S&P 500.

His first son, Robert entered the labor force out of college and worked with a consulting firm for five years. Now, at age 50, Robert has been with his current employer for five years, entering the company’s NQDC plan when he was 45. We will illustrate his benefits, assuming he stays with his employer until age 65, which is unlikely.

The second son, Sean is age 46. He, like his brother, has had a few employers before joining his current one. During his three years with the current employer, he enters a Roth-type plan, not a traditional NQDC. As we project his retirement benefits, we need only to focus on his age at retirement and not whether he remains employed with the same company because his plan is portable.

The Father’s Deferred Compensation Plan

Again, Joe, the father, began deferring money in 1988, shortly after the 1986 Tax Reform Act. Before this Act, most deferred compensation arrangements provided above-market fixed-rate interest plan (e.g., Moody’s Bond Index plus 5%). This provision was due primarily to the way plans were financed, which the 1986 Act took away.

When he entered his plan, he deferred into a portfolio that resembled his 401(k) plan. For purposes of illustration, we assume he put it all in the S&P Index to show the volatility during his accumulation and retirement.

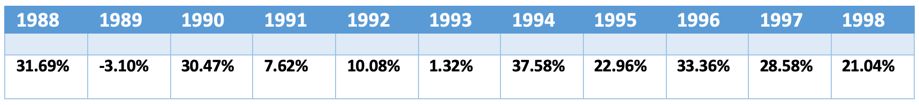

When he entered the plan in 1988, he was off to a great start— the S&P 500 earned 31.69% that year. Also, he enjoyed some great returns for the next nine years.

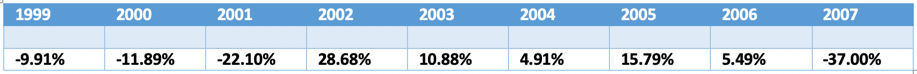

By deferring $50,000 per year, his account balance in 1998 was $2,021,847 on deferrals of $550,000. As he continued to defer his $50,000 per year, the market returns over the next nine years until retirement were not as strong, with four negative years, which included the down market of 37.00% in 2007 (see chart above).

At retirement, age 65, Joe’s account balance reached $1,819,296, which represented a return on his deferrals of 5.41%.

As he was planning out his retirement, the plan administrators assumed he would realize a 7% annual return for his 15-year payout, which would have given him $199,748 per year. But because of market volatility, his payments for the last ten years differed. Most people focus on accumulation and pay very little attention to distribution, which is a big mistake.

Joe’s projected ten years of benefits (@7%) was $1,997,748, but due to market fluctuation, he only realized $1,613,148, a pre-tax amount. He anticipated being in a much lower tax bracket. Instead, he continued at the highest bracket even into his retirement years.

New Generation: Robert Mitigates Security and Market Risk

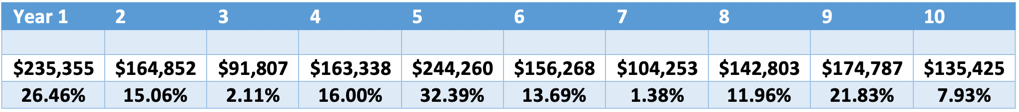

Like his father, Robert participated in a traditional NQDC plan. Beginning in 2008, he invested like his father in the S&P 500. However, his employer offered a unique fund (Collared Index) which gave him the upside of the S&P with a cap of 12% and a floor of 2%. That means if the S&P is negative, he will not lose anything.

Here’s what his returns looked like over the ten-year period.

A glance in the rear-view mirror shows that Robert would’ve been better served in the S&P 500 Index versus the Collared Index. However, one must look forward. Joe, the father, could have had a much better income stream at retirement if his plan offered the Collard Index.

Several questions you need to ask yourself: 1) Are you going to realize all up years above the cap in years to come? Will we see negative years with the S&P? Of course, we can’t predict.

The Collared Index gives Robert the upside of the market without the downside. If he wasn’t in the Collared Index, chances are he’d take a more balanced approach allocating some of his deferrals into fix-rate investment. And the probability of Robert staying with his company for ten years or longer is slim, too.

The Collared Index will also give him a benefit his father didn’t have, more predictability in retirement payments. He can stay in the market at retirement without the worry of an impact from negative years, as his father experienced in 2007.

New Tool for NQDC Risk Management

A new risk management tool, the Deferred Comp Protection Trust can help Robert mitigate the “unsecured creditor” risk at retirement. Designed by StockShield, this trust can protect Robert in the event his employer files bankruptcy.

What Gen Xers/Gen Yers Do for Wealth Accumulation

Sean, Joe’s youngest son, was born in 1964, a trailing edge boomer but on the border of Gen X. It’s instructive to compare Gen Xers with Gen Yers (aka Millennials). The Pew Research Center claims that millennials’ job tenure is no shorter than that of the prior generation with only 22 percent and 21.8 percent staying five years or more.

Because of short deferral periods, someone like Sean will not realize the true impact of NQDC compounding returns.

Moreover, one runs the risk of ending in a higher tax bracket during payout, only further compounding the problem.

Fortunately, studies show Millennials contribute more to Roth 401(k) plans than the generation before. What do these savvy Millennials know?

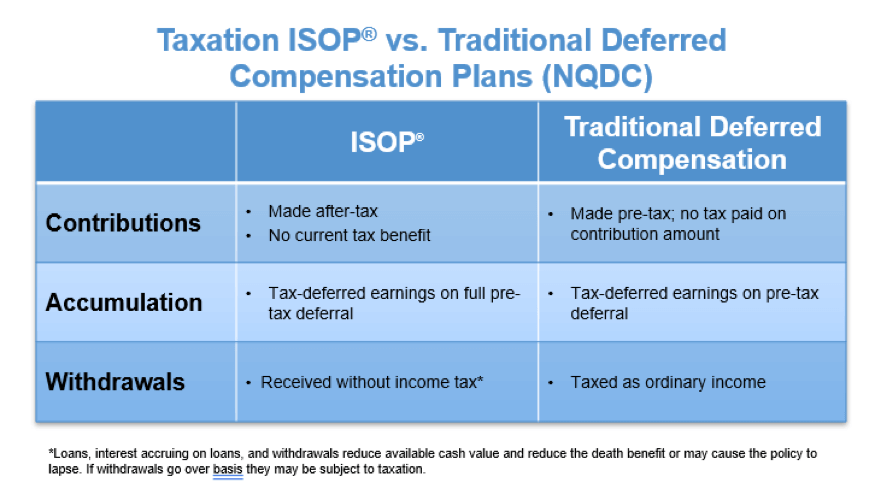

When you contribute to a traditional pre-tax plan, you earn a tax break up front. However, you must pay taxes when you take the money out in retirement.

With a Roth account, you contribute after-tax dollars, and the money you contribute, as well as the earnings, grow tax-free and distributes tax-free in retirement.

Younger workers—with lower wages and lower tax rates—stand to benefit more from the Roth option.

As our first chart above indicates, we’re at the lowest level tax rates we’ve been in for many generations. Add to this, NQDC plans don’t offer a rollover option, like 401(k)s, so you are taxed on payout under the plan’s termination benefit.

In Sean’s case, his employer offered him a Roth-type NQDC plan called the Insured Security Option Plan® (ISOP®). With this arrangement, contributions are made after tax into an institutionally price life insurance policy with the same Collared Index as his brother Robert’s NQDC plan.

The major advantage for Sean with his ISOP is portability to take with him as he changes employers during his career. What’s more, like a Roth, the ISOP grows tax-deferred and pays out income-tax-free. And the ISOP is not subject to all the restrictions of 409A or the claims of his employer’s creditors.

Let’s study ISOP mechanics. Sean makes the same $50,000 contribution annually. At tax time, he can withdraw his taxes from the fund, say $20,000 in a 40% tax bracket, without any penalty. What’s unique here is he will continue to earn the same return from the Collared Index on the money borrowed.

Therefore, he has an after-tax plan that credits earnings on the pre-tax amount. Also, his plan provides him with a $1.2 million life insurance benefit that grows to over $2 million at retirement.

At the same crediting rate as his brother, Sean will have more after-tax income and not have to worry about benefit security or future tax rate risks.

Know Your Options

For highly compensated employees, few options exist to save effectively for retirement. Many organizations offer traditional NQDC to help employees better plan for retirement. If you are in this situation, please evaluate your situation based on the factors I’ve outlined before you decide to participate.

Remember, in retirement planning, this maxim says it all:

“It’s not what you earn or accumulate, it’s what you keep.”

From the desk of Bill MacDonald, Managing Director at EBS

Executive Benefit Solutions

20 Park Plaza, Suite 1116, Boston, MA 02116

Boston | Dallas | Milwaukee | Orange County | Philadelphia| Richmond | San Diego

www.executivebenefitsolutions.com V: 617.904.9444